Setting up Python on Windows

There are many ways to set up Python on Windows—too many ways. According to the Zen of Python:

There should be one—and preferably only one—obvious way to do it.

In this spirit, I describe here what I think is the simplest way to set up Python on Windows, where “simplest” means:

- using pure Python, with no extra packages;

- enabling multiple versions of Python to exist side-by-side, without clobbering each other; and

- using no magic, meaning the user is in control and can understand everything (this is related to 1 above);

Assuming you have never installed Python, the basic steps are:

- disable the Windows Python installer;

- download Python—as many versions as you want—from python.org;

- install each version in your user directory, with the Python launcher, but without adding anything to your path; and

- using

py.exe, the Python launcher built-in to Python on Windows, within each of your projects, create a virtual environment as a subfolder in the project folder, specifying the Python version needed.

I conclude with some tips on using VS Code and a discussion of alternative methods of setting up Python on Windows.

Step 1: Disable the Windows Python installer

If you type python or python3 at a command prompt in a new Windows 10 installation, you land at a link at the Microsoft Store for installing Python. This is supposed to make things easy for beginners. It sort of does, but at the expense of potentially making it harder to manage multiple Python versions. Installation via the Microsoft Store smells like magic to me, so I don’t recommend it.

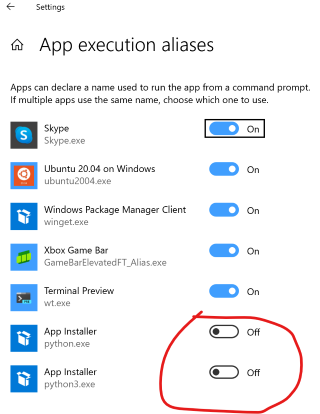

To disable this behavior, go to Start→Manage App Execution Aliases and turn off the toggles for App Installer - python.exe and App Installer - python3.exe, like so:

Step 2: Download Python from python.org

To avoid magic, download Python directly. You can install as many versions as you like. The order of installation doesn’t really matter, though (as discussed below) it may affect the behavior of py.exe, the Python launcher.

Step 3: Install Python in a user directory, with launcher

By default, when you install Python with an installer from python.org:

- Python will be installed in a user-specific directory rather than a system directory,

- Python will install the Windows launcher,

py.exe, for all users (inC:\Windows), and - Python will not change your system path.

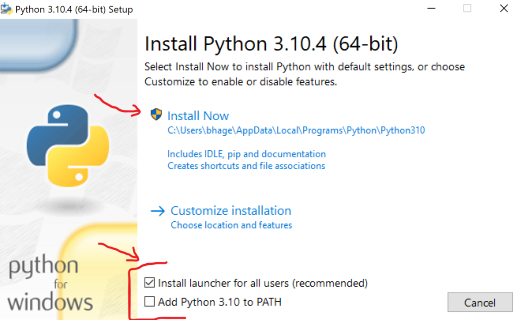

Accept these defaults. The installation screen should look like this:

After you select Install now, the next screen will ask if you want to Disable path length limit so that your path can exceed the system’s 260-character limit. I suspect this is unnecessary, since we are deliberately not adding Python to the path. But I’m not sure there’s a downside. Use your judgment.

Note: The next time you install some version of Python, the Install launcher for all users option will probably be grayed out, because the launcher will already be installed. If it’s grayed out, that’s fine. If it’s not grayed out, leave it selected, and the launcher will be updated.

Step 4: Use py.exe to create virtual environments

The Python launcher py.exe allows you to easily work with multiple different versions of Python. Basic commands (executed at a command prompt):

py— launches the latest version of Python you have installed.- There’s a tiny bit of magic here. When you install a newer version of Python, the launcher will automagically update itself so that when

pyis run with no arguments, it launches the latest version of Python. - You will typically not use this by itself, because you will be using

pyto create virtual environments, rather than to run Python outside of an environment.

- There’s a tiny bit of magic here. When you install a newer version of Python, the launcher will automagically update itself so that when

py --list— shows you all installed versions of Pythonpy --help(orpy --help | moreto get info a page at a time) — provides command-line switches forpyand forpython(which is called bypy)py -X.X(for instance,py -3.10, orpy -3.9) — launch versionX.Xof Python.- With no arguments, this launches the Python REPL. With arguments, this is how we execute modules or scripts. It’s the key to creating virtual environments.

Creating virtual environments with py.exe and venv

- At a command prompt, create a project directory and navigate into to it. For example (here

>is the prompt):> cd C:\my_projects > mkdir project1 - Within your project directory, use

pyto create a virtual environment, specifying the python version and the directory name. For example:> cd C:\my_projects\project1 > py -3.9 -m venv p1_venv - Things to note:

- You can substitute any installed version for

-3.9in this statement (you don’t need to specify the minor version). - The environment name

p1_venvis arbitrary.- This will create a subfolder

\p1_venvwithin theC:\my_projects\project1parent folder. - This structure—a top-level project folder with a virtual environment in a subfolder—is the preferred structure for doing Python development with VS Code.

- This will create a subfolder

- A lot of people use

venvor.venvfor the environment name. I dislike this convention because the namevenvor.venvis totally uninformative—it shows up in your prompt to tell you that some virtual environment is activated, but not which one.- There might be other good reasons for always using

venvor.venvto name a virtual environment. Perhaps it makes other setup tasks easier. But I’ve never seen anyone explain the benefits (if they exist).

- There might be other good reasons for always using

- You can substitute any installed version for

Using the virtual environment

If your virtual environment is at C:\my_projects\project1\p1_venv, activate it as follows:

> cd C:\my_projects\project1\

> .\p1_venv\Scripts\activate

You should now see the virtual environment name before the prompt, like so (assuming your working directory is also shown at the prompt):

(p1_venv) C:\my_projects\project1>

To deactivate, just enter deactivate at the prompt.

Using Powershell aliases to simplify using virtual environments

Creating Powershell aliases can make using virtual environments easier. Building on the example above, you might put something like this in your Powershell profile (a user- and host-specific profile is at $profile.CurrentUserCurrentHost and is called Microsoft.PowerShell_profile.ps1 wherever it’s found1):

# create function and alias that calls function

# p1 will change to project directory and activate environment

Function Use-project1 {

cd "C:\my_projects\project1"

.\p1_venv\Scripts\activate

}

Set-Alias p1 Use-project1

Using VS Code with Python virtual environments

The VS Code Python extension is designed to work well with virtual environments, but I found the documentation confusing. While answering my own question on StackOverflow, I figured out what I think is a good workflow. This assumes you have already created your virtual environment in a subfolder within your project directory:

- At the command prompt, navigate to your project directory (the directory that contains your virtual environment). (You could create an alias for this navigation if you like.)

- From there, execute

code .

This will open VS Code, using your project directory as a workspace. If you create or open a Python file in the workspace, VS Code will automatically detect and activate the virtual environment in the subfolder in the workspace (i.e., project directory).

You might be tempted to use a virtual environment as a project directory, that is, as the root of your workspace. Don’t do it. The VS Code documentation should say2):

Note: Your Python virtual environment should always be a subdirectory within a VS Code workspace. Opening the virtual-environment folder directly, as the root of the workspace, might cause problems.

You can create a Python virtual environment within a workspace by using VS Code’s built-in terminal. But I prefer to create the environment first, outside of VS Code, because that way, I know exactly what’s happening.

If for some reason VS Code does not detect your virtual environment, you can manually direct VS Code to it by opening the command palette with Ctrl-Shift-P, entering Python: Select Interpreter, and navigating to python.exe found in the \Scripts subfolder of the virtual environment. You should only need to do this once.

Alternative methods for setting up Python on Windows

The pyenv project

There is a whole project, pyenv for Windows, specifically designed to allow you to manage multiple versions of Python on Windows. It’s an impressive piece of work, and if it interests you, check out a very detailed Real Python tutorial on using it.

I prefer not to use it for two reasons:

- I don’t see the need, given the existence of

py.exe. And - It only works well if you use it exclusively. For instance, if you have previously installed a Python version directly, without using

pyenv, thenpyenvwill not detect the installed version.

Using venv or virtualenv (or something else)

Since Python 3.3, venv has been the tool in the Python standard libary for creating virtual environments. For simplicity’s sake, like the author of the second answer to this StackOverflow question, I (and apparently Guido van Rossum) prefer using it.

You will, however, see lots of references to using virtualenv for creating virtual environments. It existed before venv and is apparently your only option if you use Python 2.x. And pyenv includes even more related tools. These various tools are summarized in the first answer to the StackOverflow question cited above. I disagree with the answer, but it’s full of useful information.

1For more on Powershell profiles, see footnote 1 in my post about setting up a Windows dev environment. ↩

2Instead of this very clear warning, the VS Code documentation says:

Note: While it’s possible to open a virtual environment folder as a workspace, doing so is not recommended and might cause issues with using the Python extension. ↩